There was an explosion of online reactions to House Republicans passing their Obamacare repeal and replacement bill Thursday, but not all of the social media talk was accurate. To help parse fact from fiction, we’ve broken down some of the most prominent takes.

The American Health Care Act has not been passed by Congress and Obamacare isn’t going away — yet.

The AHCA has passed through the House of Representatives, but it still needs to go through the Senate and be signed by President Donald Trump before it replaces Obamacare. And senators have been open about their intentions to amend the bill. They could radically change it or the bill could fail altogether.

The GOP health care plan does not make rape a pre-existing condition and assault survivors won’t lose their health care.

This claim, which has been flying around Twitter and Facebook, seems to stem from pre-Obamacare reports of domestic abuse victims being denied health insurance. The argument goes that returning to the pre-Obamacare system will bring this practice back.

This analysis ignores several factors. First, the AHCA doesn’t allow insurance companies to deny people coverage because they have a pre-existing condition. States can apply for waivers that would allow them to raise prices on people with pre-existing health conditions — but not ban coverage — and those waivers would have to be approved by the Department of Health and Human Services.

Even in those cases, however, all but two states — Idaho and Vermont — already ban insurers from factoring domestic abuse into premium costs. Even before Obamacare, charging abuse victims more for their insurance premiums was extremely rare; while the practice was prevalent as late as the 1990s, there was little sign of it by the late 2000s.

However, while rape will not be counted as a pre-existing condition itself, use of services that result from a sexual assault (such as mental health services and STD treatments) could potentially cause someone to face higher premiums in states that opts for waivers.

The AHCA will make it a lot harder and more expensive for many women to get abortions.

A centerpiece of the AHCA is that it provides people refundable tax credits of $ 2,000 to $ 4,000 per year, depending on their age, for people who buy their own insurance plans. But not only can that money not be used for abortions themselves, it can’t even be used to pay for insurance plans that include abortion coverage, likely meaning that most plans won’t. California requires all insurance plans to cover abortions, so their residents won’t be eligible for the tax credits.

The bill also takes away federal funding from Planned Parenthood and its affiliates. Under current law, these funds are reimbursements for non-abortion services provided to Medicaid enrollees; without them, low-income women may not be able to afford services. The Congressional Budget Office projects the loss of federal funding will cost Planned Parenthood $ 178 million this year.

Being a woman is not a pre-existing condition under the Republican plan, but some issues that affect women are.

Before Obamacare, insurers could charge women more for insurance than men. Obama’s law banned that practice and the AHCA keeps that ban in place. Under the AHCA, insurers still cannot charge women more than men.

That said, there is some truth to the claim’s underlying point. Under the current system, insurers in the individual market must cover certain essential services, including maternity care. Under the new GOP plan, states could apply to waive this rule. That would allow insurers to offer cheaper plans without maternity care, thus making plans that do cover pregnancy more expensive. Also, a woman who undergoes a C-section, which can lead to future health complications, could face higher prices in a state that chooses to waive pre-existing condition protections.

Moments before the AHCA passed the House, Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi described the legislation as a tax break disguised as a health bill. Whether or not you buy the rhetoric, it’s indisputable that one of the biggest impacts of the AHCA is moving hundreds of billions of dollars from health for the predominantly poor into tax cuts for the predominantly rich.

President Obama’s Affordable Care Act provided states federal funding to expand Medicaid to cover more low-income people. The Republican bill rolls back this expansion. The result, according to the Congressional Budget Office, is a cut of $ 880 billion to Medicaid over the next decade. Over that same time period, the AHCA provides tax cuts of almost $ 600 billion, the vast majority of which benefit Americans making over $ 200,000.

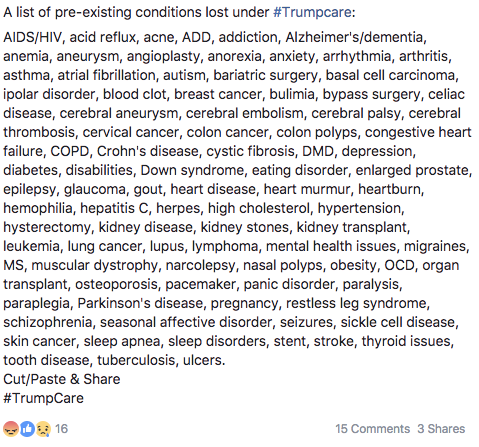

You won’t lose coverage because of a pre-existing condition, but your insurance could be expensive. And there is no official list of pre-existing conditions either.

Many people are posting that they or their loved ones will imminently lose insurance because they suffer from a pre-existing condition. It is true that under the AHCA, some people with pre-existing conditions will likely face higher premiums, but there are some major caveats to consider.

First, the AHCA is not taking away your existing insurance plan. In theory, people with pre-existing conditions can protect themselves from rising prices by staying insured, because insurers can only jack up prices on new enrollees or people who have let their coverage lapse for more than 63 days. However, there are concerns that healthy people will opt into cheaper but skimpier plans and cause prices to skyrocket for those who don’t have that luxury.

For those without insurance, or who lose their coverage, it will depend on what state you live in. The AHCA gives states the ability to request waivers from the rule that prevents insurers from jacking up prices on people with health ailments. And it is unclear how many states will actually do that. The AHCA itself is predicated on the assumption that only a small number of states will exercise these waivers, but we don’t know if that’s the right guess.

And states that do waive those rules need to put money into high-risk pools that are supposed to cover sick people who get priced out of the the individual market. The big question is whether these pools will be adequately funded for a change.

Many people are operating under the assumption that passing the AHCA would mean a return to the days insurance companies had practically unlimited discretion in most states to deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions. But that’s not necessarily true. Health and Human Services still needs to sign off on the regulatory framework of any states seeking a waiver, and we don’t yet know what that will look like.

What’s more, there is no official list of what will and what won’t qualify as a pre-existing condition. In the states that do get waivers, insurance companies will get to decide what ailments should cost more.