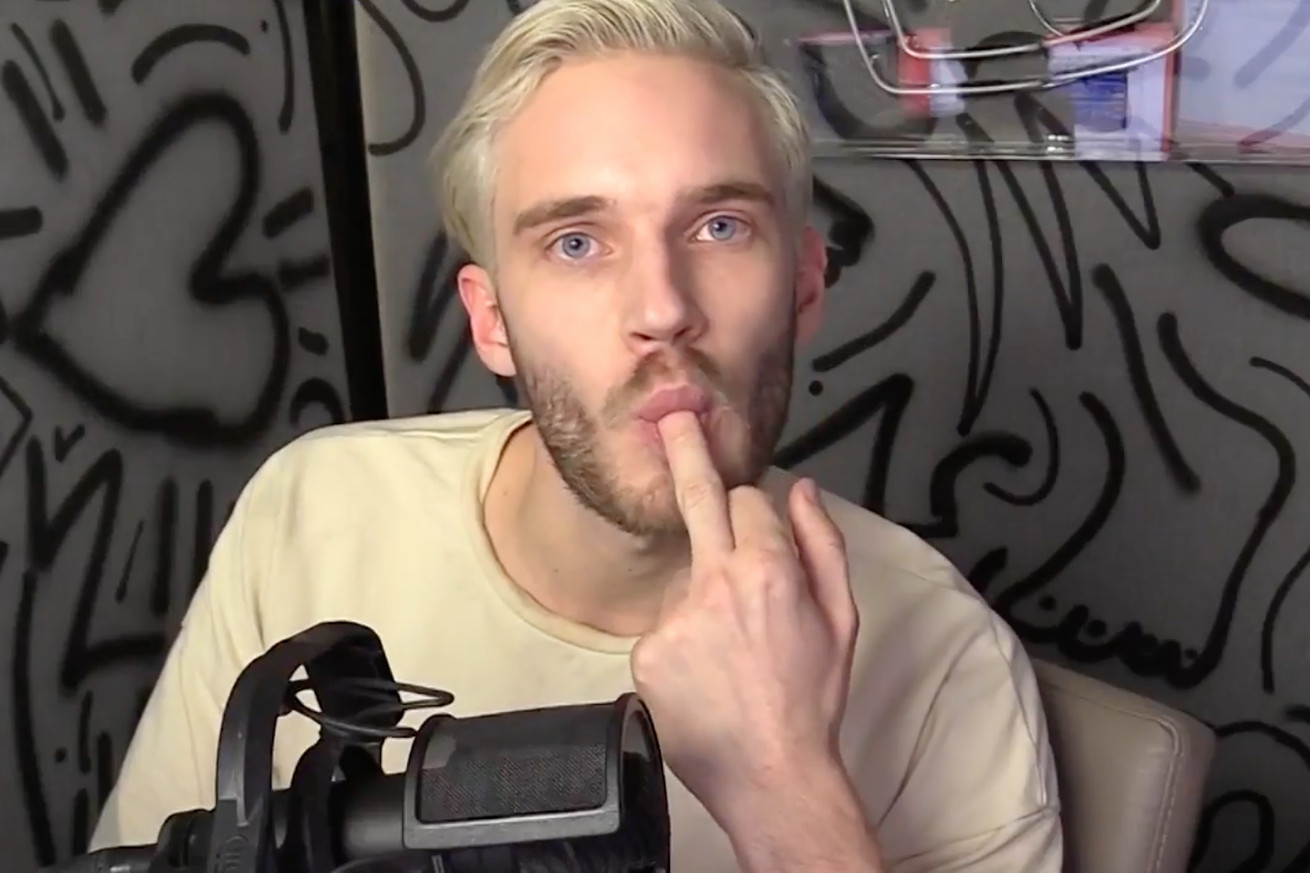

Earlier this week, YouTube streamer PewDiePie lost a contract with Disney because of some Nazi references in his videos and one absurdly ill-considered attempt to make a joke out of genocide. But as a variety of people have pointed out, this controversy is only the latest example of a pushback against “political correctness,” often centered around the “manosphere,” the “alt-right,” and the uglier parts of video game culture.

In a well-argued BuzzFeed essay, writer and Screener editor Jacob Clifton described PewDiePie’s actions as representative of a larger masculine identity crisis, and urged readers to engage with rather than demonize the people caught up in it. “The whiny self-importance and self-indulgence of white male rage,” writes Clifton, “is so repugnant that it’s nearly impossible to see through. But we won’t heal, and they won’t heal, if we don’t try.” There’s merit in all this. But after a point, it’s tiresome to constantly hear the same revelation about how we need to understand white male rage — when it feels as though that’s all we talk about.

Clifton is talking largely about confronting people you know in real life, not getting into the heads of random internet users. But over the past few years, we’ve gotten a great deal of the latter. Anthropological dives into reactionary horror are a subgenre of internet writing: no meme goes un-analyzed, no men’s rights activist un-interviewed, no racist logic unexplained.

There are meaningful points to make about these things. For example, it’s useful to know that someone like PewDiePie is almost certainly not a Nazi, but his jokes end up giving cover to actual bigots, while creating an environment in which bigotry feels increasingly normal. We know that the internet’s ability to create self-contained, self-reinforcing spaces makes that whole process easier.

But after a certain point, raising awareness risks presenting reactionary internet spaces as an endlessly fascinating linchpin of online culture, a hip countercultural rebellion against present-day norms. Even if people in them are presented as misguided, they’re also implicitly depicted as weird and edgy and pushing boundaries, and definitely not just posting variations of “Hitler did nothing wrong” and other warmed-over slogans from some particularly bad Cards Against Humanity deck.

This is why people end up calling Donald Trump — a real estate tycoon — and Milo Yiannopoulos — a younger Rush Limbaugh with better hair — punk rock, because they’re crudely transgressing social boundaries and creating chaos in the process. But Nazi symbolism, semi-ironic misogyny, and nihilistic misanthropy are no longer meaningfully transgressive; in fact, they’ve been in perennial rotation for decades. We don’t look back on the birth of punk rock fondly just because it made people angry, but because it produced something the world had never seen.

Meanwhile, the people who seem to be most genuinely alien to older generations (including me, sometimes) aren’t the “edgelords” picking up the dusty banner of the ’70s punk swastika. They’re the much-derided “special snowflakes” that have college professors and pundits doomsaying about the rising threat of trigger warnings and safe spaces. They’re the aggressively cute proponents of “cybertwee,” the soft and socially aware reaction to three decades of increasingly tired ’80s chrome-and-circuits loners. We’ve had several decades of young men trying to replicate a 20th century ideal of rebellion, but the strangest and most extreme thing that a group can be right now is radically, intensely dedicated to emotional intelligence and the notion of inclusivity.

There’s interesting coverage of these spaces, including both their beneficial sides and their toxic ones: The Daily Dot takes things like Tumblr and fan fiction culture seriously, and The New Republic dived into “relatable” teen blogs last year. But lefty Tumblr blogs don’t get as many serious deep-dive profiles as men’s rights advocates or reactionary subreddits, and their minor memes don’t get the same wide-ranging publicity — like the massive news cycle dedicated to the alt-right triple parenthesis, a nasty in-joke that got presented to the world as a diabolically clever harassment scheme.

When people in non-stereotypically masculine spaces come under criticism, warranted or not, the reaction is often as chiding and dismissive as it is horrified. Take, for example, the many articles about left-wing campus activism. The people involved are often presumed to be privileged pseudo-intellectuals looking for something to complain about, not people who deal with things like racism or misogyny on top of feeling like they’re being ignored or left behind by modern capitalism. (Never mind that plenty of right-wing reactionaries are financially comfortable.)

“Coastal elites,” one argument goes, need to understand white male rage in order to put liberalism and media coverage back in touch with ordinary people. Kindness and awareness can certainly be helpful. But there’s no shortage of people explaining this phenomenon, and talking about people isn’t the same as talking to them. They’re not the only ones who feel disenfranchised, either — just the ones whose voices we’re most inclined to hear.

Media outlets and groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center monitor online forums for hate group activity that could appear online before breaking into real-world violence. But this doesn’t necessitate producing blanket coverage of alt-right cultural quirks. It’s useful to know about these spaces, but I’m not convinced that constantly putting them on display is much of a disinfectant. If anything, it makes it easy to romanticize them or paint their inhabitants as brilliant masterminds, fueling their sense of self-importance and persecution complex.

To be clear, I’m as responsible for doing this as anyone else. I’ve spent a lot of time consuming stereotypically white male rage-y culture, and I’m more primed to treat it as more worthy of exposure and analysis. (I’m also quite fond of cyberpunk and ‘70s punk bands.) But increasingly, all of this feels redundant — the sort of cultural bubble I should do more to break out of. It’s like hearing a cover band play a Sex Pistols song; the lyrics might still offend, but I’ve heard them all before. While it might be easy to forget right now, it wasn’t even deliberate edginess that first made PewDiePie’s name as a game streamer. It was an enthusiastic willingness to do things like scream himself silly at horror games — to make a joke out of his own vulnerabilities, not lash out at the world.